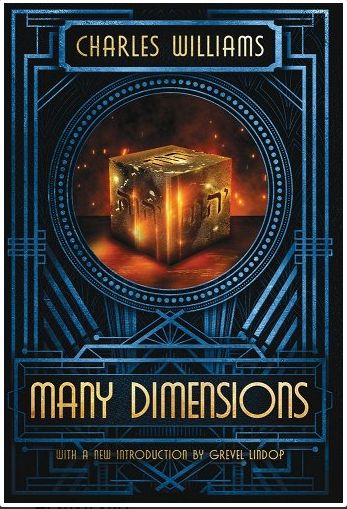

Many Dimensions is Charles Williams’ second novel – published in 1931 – and it is quite good. In an earlier post, I reviewed his first novel, War In Heaven. Williams was an Inkling – the group of writers and thinkers that included J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and Owen Barfield. While Williams wrote fantasy, his work is about as far from Middle Earth and Narnia as one can imagine.

The story begins with Sir Giles Tumulty, who returns from War In Heaven. He is a thoroughly repellent character, who is completely materialistic and amoral. In Many Dimensions, he has, through unexplained but probably unethical means, obtained the Stone of Solomon. It is a small cube of milky white substance with the letters of the Tetragrammaton inscribed on its faces. The stone seems to have unlimited powers, including the ability to transport its bearer to any location on earth instantaneously. Giles also suspects it can travel through time, and he intends to test his thesis on some innocent subject. He is being pursued by agents of the Persian government, who have safeguarded the stone for many centuries.

As Giles and his nephew, Reginald Montague, begin an analysis of the stone, they soon discover that they can strike off pieces of it which are identical to it in mass, size, appearance, and powers, while the original stone maintains its mass. Reginald immediately starts cooking up schemes to profit off of this seemingly limitless source of transportation.

Meanwhile, England’s Chief Justice, Lord Arglay, who is a brother-in-law of Sir Giles, comes into possession of one of these stones. He and his secretary, Chloe Burnett, soon realize how dangerous the proliferation of these stones of infinite power is to world stability. Arglay, Chloe, and the Hajji – a very old and wise Persian – decide to oppose Sir Giles, various government agencies interested in the stone’s millitary and intelligence applications, an American millionaire and his wife whom Montague snookered into paying 70,000 guineas for one, and various other antagonists who all want stones for selfish reasons.

I have already mentioned how awful a person Sir Giles is, but he ends up being one of those villains you love to hate. As Lord Arglay puts it,

“Giles always reminds me of the old riddle, ‘Would you rather be more abominable than you sound, or sound more abominable than you are?’ The answer is, ‘I would rather be neither, but I am both.'” (Charles Williams. Many Dimensions (Kindle Location 598). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.)

Williams gives Giles terrific epithets, curses, and insults to hurl at everyone around him:

“broken-down Houndsditch sewer rat”, “Blast your filthy gasbag of a mouth!”, “Encyclopedias are like slums, the rotten homes of diseased minds”, “you baboon-headed cockatoo”, and “half-caste earthworms” are just a few examples of his picaresque language.

That said, Sir Giles is quite evil in his single-minded pursuit of knowledge and power. In a conversation with some government secretaries, he illustrates what a monster he is:

‘You might,’ Sir Giles said, ‘use it as the perfect contraceptive.’ Mr. Sheldrake looked down his nose. The conversation seemed to him to be becoming obscene. ‘Under control,’ Lord Birlesmere said thoughtfully, ‘always, always under control. We must find out what it can do; you must, Sir Giles.’ ‘I ask nothing better,’ Sir Giles said. ‘But you Puritans have always made such a fuss about vivisection, let alone human vivisection.’ ‘No one,’ Lord Birlesmere exclaimed, ’is suggesting vivisection. There is a difference between harmless experiments and vivisection.’ ‘I can have living bodies?’ Sir Giles asked. ‘Well, there are prisons — and workhouses — and hospitals — and barracks,’ Birlesmere answered slowly. (Charles Williams. Many Dimensions (Kindle Locations 1850-1856). Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.)

One thing I admire about Many Dimensions is Williams’ thoughtful treatment of the impications of time travel. Lord Arglay soon realizes that if a person were to use the stone to travel back to a time before he or she had the stone, they would have to live up to the point where they got the stone and traveled back in time. In other words, they would be trapped in an endless loop, forever reliving the point in time where they decided to go back in the past. Sir Giles reaches the same conclusion, and he tricks a gullible lab assistant into doing just that. Giles attempts to go thirty minutes into the future himself, but the stone only takes him ten minutes. He is soon haunted by the uncertainty of whether he is actually experiencing life, or recalling his memories of the past ten minutes.

As in War In Heaven, spirituality pervades Many Dimensions. However, where the spirituality in War In Heaven is explicitly Christian, in Many Dimensions it is a strange mix of Sufism and Judaism. The hero, Lord Arglay, is an agnostic who gradually comes around to believing in God through the faith of Chloe. The stone itself seems to be the First Matter, that which God created from nothing.

If I go any further, I’ll have to give spoilers, and I don’t want to do that. Suffice it to say that Many Dimensions is an excellent tale that leaves the readers pondering some weighty concepts. I highly recommend it to readers who enjoy considering the implications of what would happen if mankind had access to something that granted its every wish. Williams makes a strong case that the result would not be a utopia, but rather a hell.